Veering off course:

Transportation emissions & the climate crisis

Trains, planes, and automobiles make the world seem smaller than it used to be at a steep cost. Their emissions, representing 16% of all greenhouse gases, are warming the planet.

When we changed how we travel

The mechanization of transportation made it practical and safe to travel further and faster. It revolutionized personal mobility and the commercial freight industry. It allowed us to get where we wanted to, no matter how far away and it fuelled the global economy, allowing us to receive products produced from anywhere in the world.

That transition came at a cost. The amount of exhaust fumes created as a by-product of this has grown exponentially over the last century; these exhaust gases directly increase the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

Transportation emissions add 8 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere every year, representing 16% of all emissions. There are indications that this problem is getting worse rather than better, as motorists in less developed economies increase the demand for gasoline petrol vehicles, causing their numbers to grow despite the increasing adoption of electric vehicles elsewhere.

With most CO₂ staying put for at least a thousand years, tailpipes are driving up the average global temperature fast and furiously.

Before mechanization, when humans and horses powered mobility, their carbon emissions were practically nil. But movement was restricted and slow. A horse and wagon could travel 10-30 miles a day, depending on terrain and weather. Transatlantic voyages lasted weeks and were a hotbed for diseases.

It was only towards the end of the 19th century, with the help of steam-powered engines, that transatlantic voyages became practical and cost-effective for passengers and cargo. My great-grandparents, who immigrated to Canada in 1921, made the journey on a coal-burning ocean liner called the S.S. Megantic.

Our growing carbon footprint from transportation emissions

Had my great-grandparents made the journey from the United Kingdom to Canada in 1830, their sailing boat would have caused almost zero CO₂ emissions. However, it would have taken 5 to 6 weeks for them to make the trip.

In 1921, it took seven days to cross the Atlantic. The twin quadruple-expansion-compound marine engines that powered the boat consumed about 1.34 lbs of coal per hour per indicated horsepower. The S.S. Megantic had a rating of 1,180 NHP.

2 engines x 1.34 lbs per HP per hour per engine x 1,180 HP X 24 hours x 7 days per voyage x 1 U.S. tonne / 2000 lbs = 265.6 tonnes of coal per voyage.

Assuming each tonne of coal burnt releases 4,172 pounds of CO₂, the total CO₂ released would have been 554.1 tonnes for the trip. The ship could carry 1,135 passengers, and the distance from London to Montreal is 5,227 km. So, at full capacity, this would translate to 84.7 g of CO₂ per passenger per kilometer.

In 2022, you can fly from London, UK, to Montreal, Canada, in 7.5 hours. In the last century, the world has shrunk by a factor of 20 and by 80 in the last two. However, the carbon footprint has grown substantially per kilometre, more than tripling by today’s levels for the same trip.

Comparing the emissions by fuel type

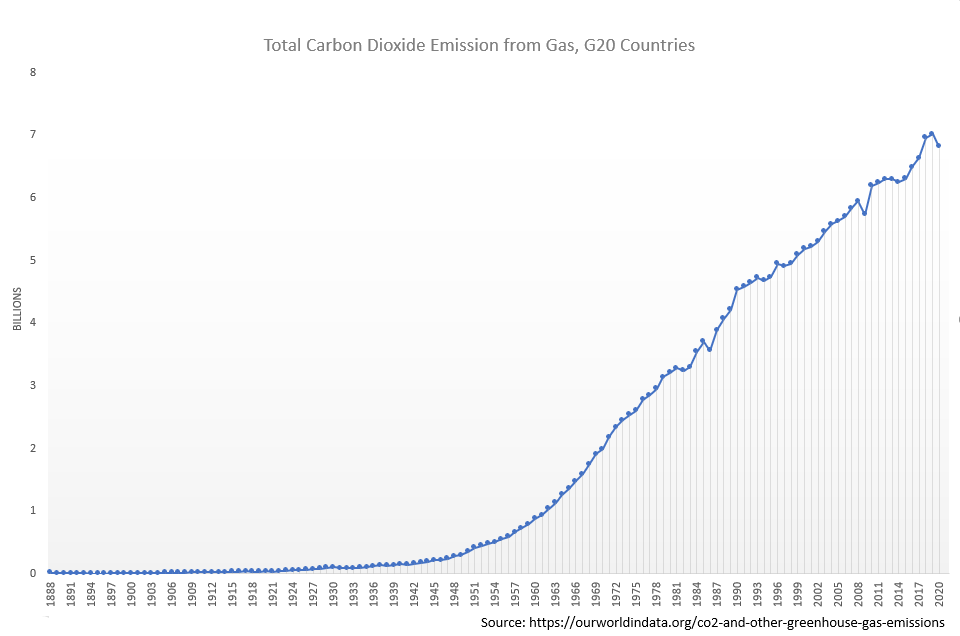

Comparing the CO₂ emissions by fuel type per capita in 1820, 1920, 1970 and 2020 – note the rising emissions from gas and oil. In the last century, gas-related emissions have gone up by almost a factor of 50, oil by 8, while coal has remained stable.

Over this same period, the amount of CO₂ emissions from aviation and road passenger vehicles has continuously and relentlessly increased.

A recent study suggests one person will die for every increase of 4,434 metric tonnes of CO₂ produced compared to 2020 levels. That is equivalent to the amount released on average annually by 70 drivers in the United States[1]. Or 80 London- Montreal roundtrip flights of 200 passengers.

According to International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)[2], 2019 saw a 4.9% increase in scheduled revenue passenger kilometres performed, adding 60 million tonnes of emissions[3]. If this level of growth returns to the aviation industry, it would potentially cause 13,725 additional deaths.

The boat they travelled on, the SS MEGANTIC of Liverpool at Aberdeen Wharf, Millers Point, Sydney, Photograph was taken by Frederick Garner Wilkinson.

The 8 billion-tonne question

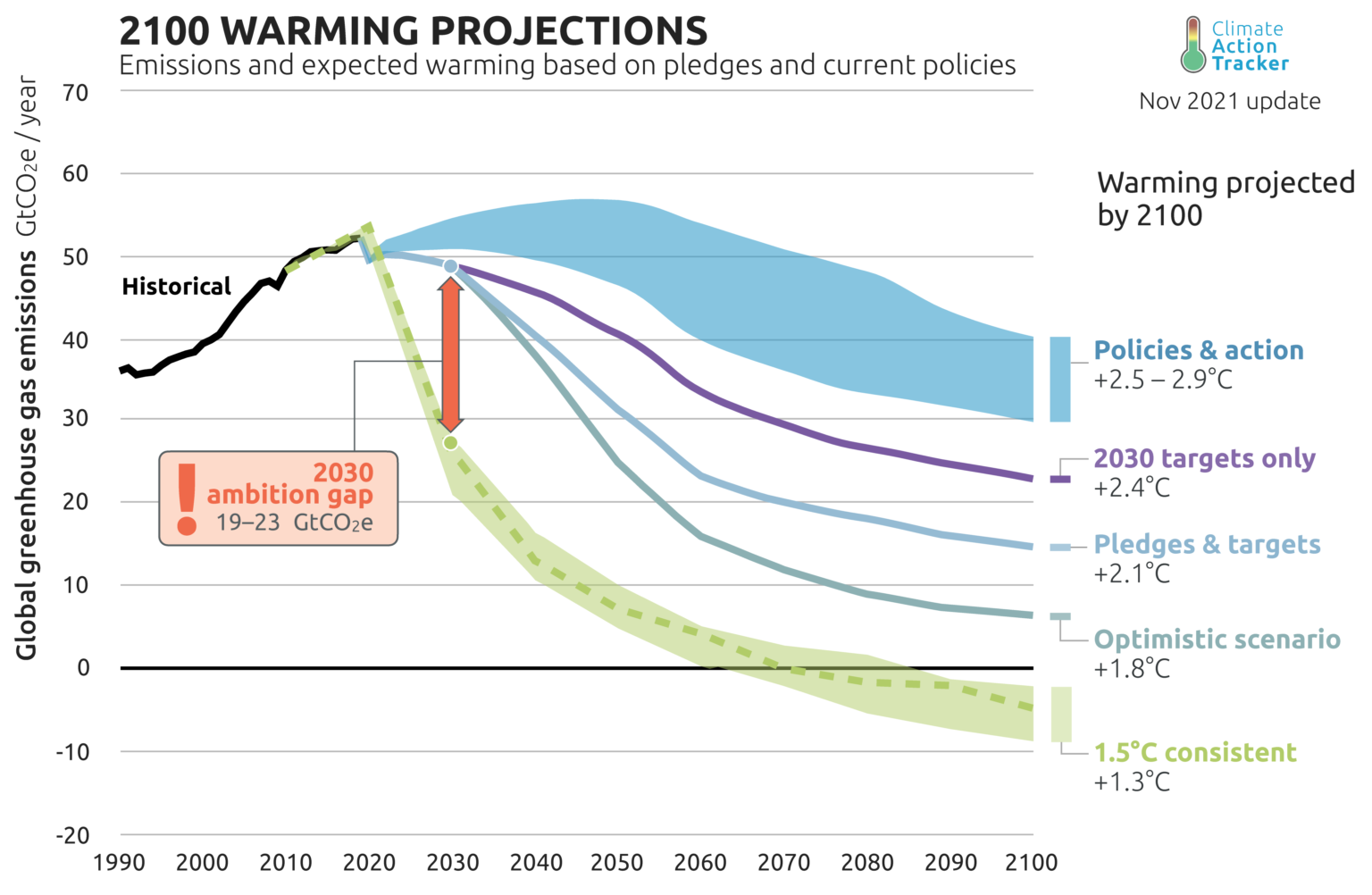

The current predictions from Climate Action Tracker are bleak: rising carbon emissions, causing a greater than 1.5ºC degree increase in global average temperature by 2050 or sooner. We are veering off course towards a climate catastrophe.

The amount of carbon dioxide emitted due to transport must start decreasing. Reaching net-zero carbon by 2050 and avoiding the irreversible damage threshold of 2ºC degrees of warming requires a 20% reduction in emissions by 2030.

Can emissions get back on track? Can significant parts of transport be decarbonized with existing technology? What are the barriers?

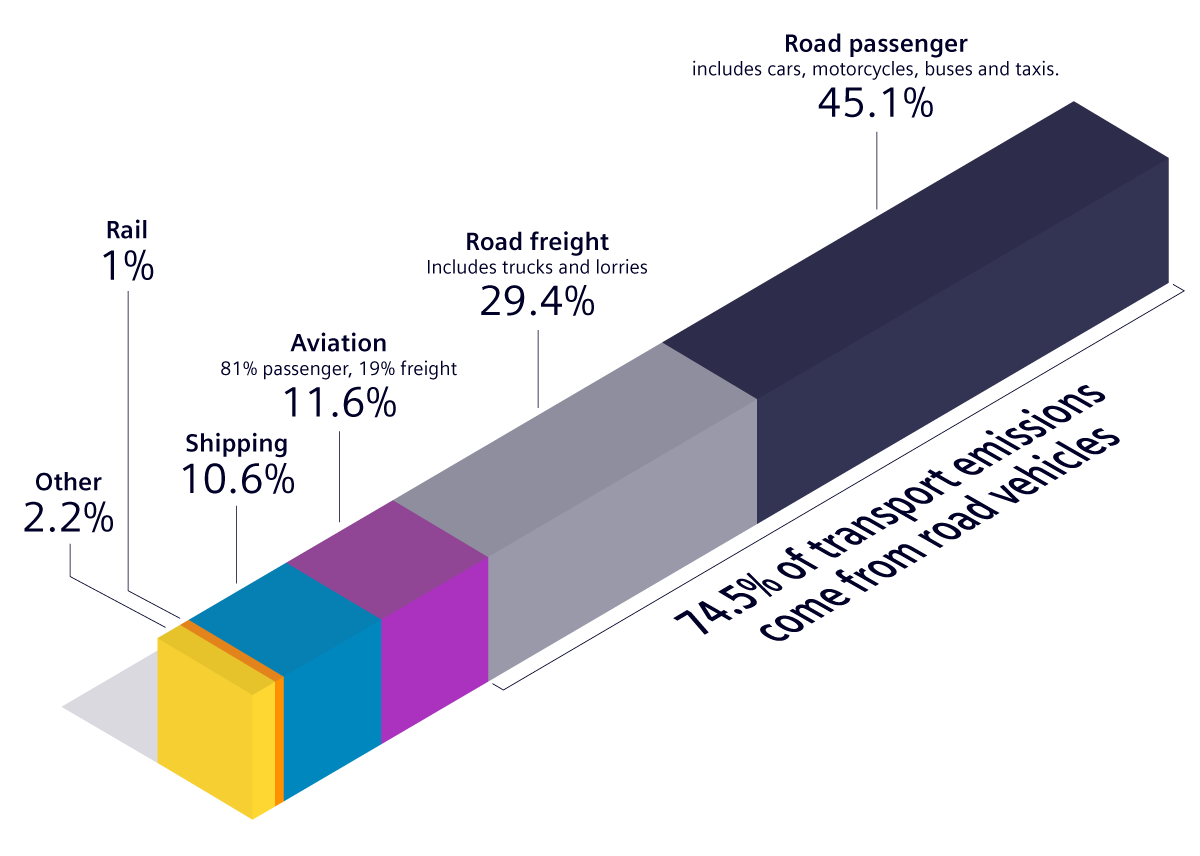

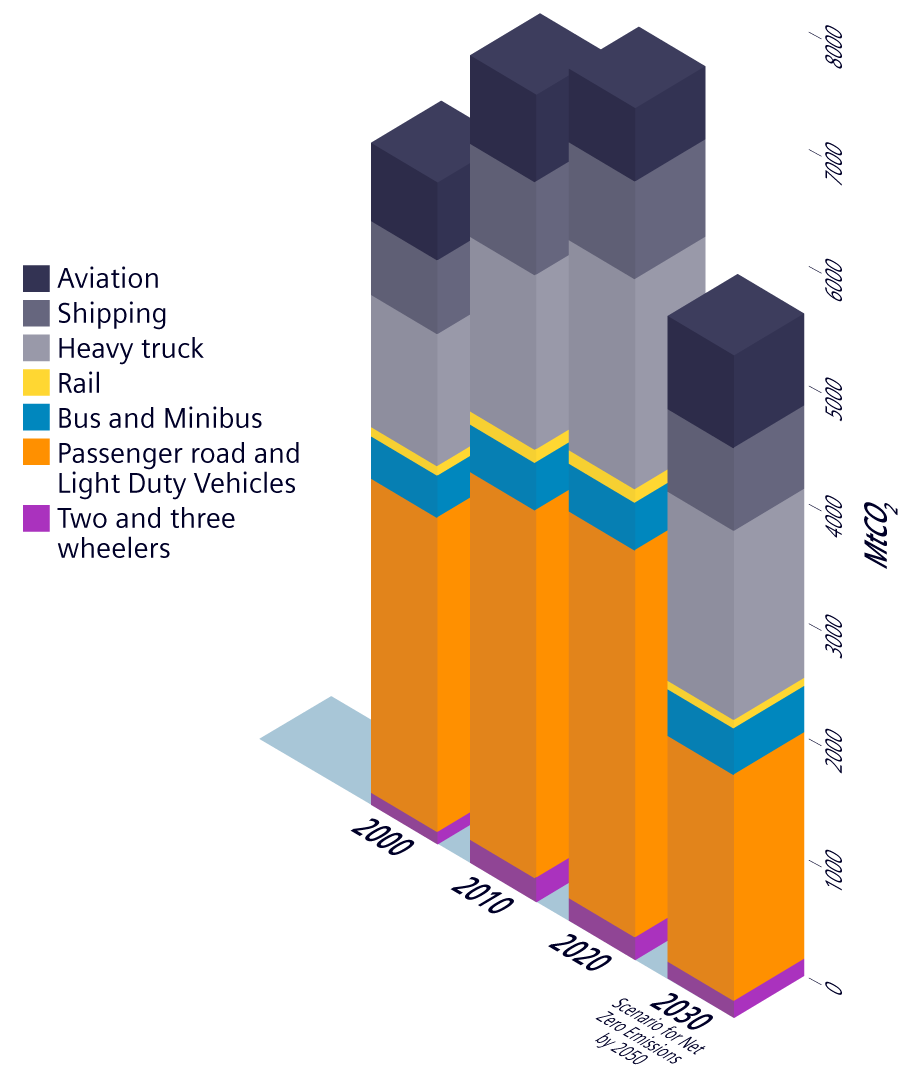

Four significant subsectors emit 95% of the greenhouse gas emissions due to transportation. Passenger road vehicles are responsible for 7% of the annual global CO₂ emissions.

Current policies presently in place are projected to result in a 2.7°C increase. Source Climate Action Tracker – https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/

Global CO₂ emissions from transport

This is based on global transport emission in 2018, which totalled 8 billion tonnes CO₂. Transport accounts for 24% of CO₂ emissions from energy.

Data Source: Our World in Data based on International Energy Agency (IEA) and the international Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT).

Road passenger vehicles

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ICE vehicles faced competition from steam and electric powered engines. It was not a foregone conclusion which technology would dominate the automobile industry.

Steam-powered vehicles had limited energy storage capacity and took forever to startup. They also had a rather inconvenient habit of exploding.

The electric cars of that era were quiet and easier to operate than their ICE counterparts. Yet, they suffered from familiar drawbacks: the small energy storage capacity limited their range and required a long time to recharge.

Internal combustion engine vehicles were not vastly superior

To clarify, they were noisy, unreliable, mechanically complex, and difficult to start. For a brief period, electric and ICE vehicles had comparable ranges on one charge or one tank of fuel.

However, innovations came quickly. In the 1920s, fuel economy was improved and gave ICE vehicles a range advantage. The cumbersome ignition issue was resolved. Henry Ford’s Model T added another advantage: price point. Using assembly lines to manufacture the car made it almost four times cheaper than electric vehicles. With that, steam and electric cars started to disappear.

Although combustion vehicles dominate the road transportation market, their time is limited. Many governments have established legislation to restrict or prohibit the sale of fossil-fueled vehicles in the next decade.

CO₂ emission from gas has grown steadily with the invention and popularity of internal combustion engine vehicle

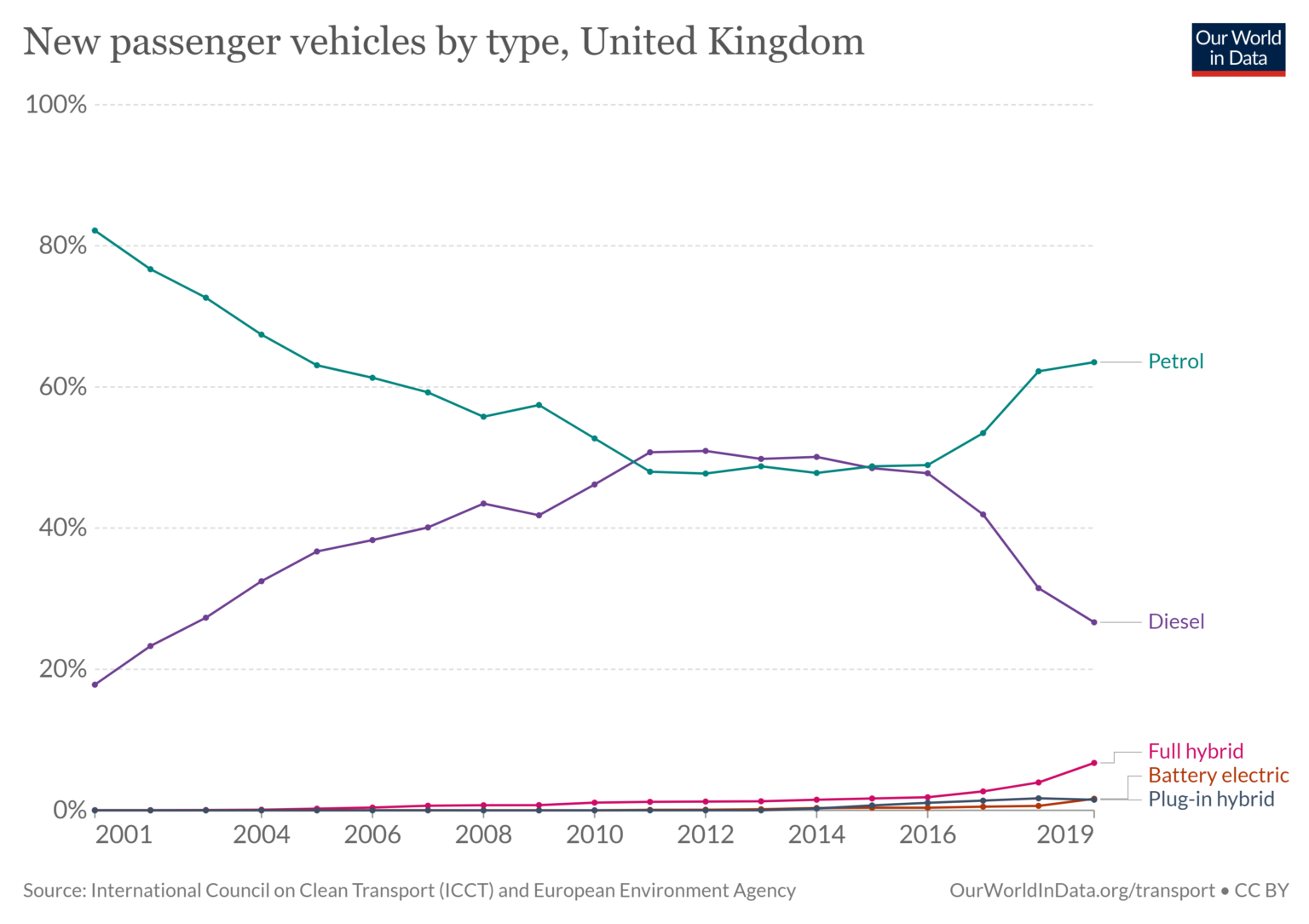

The sluggish adoption of electric vehicles

Electric vehicles have significantly improved over the past 20 years. In 2001, the Toyota Prius became the first to make significant enduring market penetration. And while it is a success and better for the environment than a pure ICE vehicle, as an HEV, it is not an emission-free car. In truth, there has been minimal adoption of anything but gasoline and diesel-burning vehicles, despite the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) growing warnings since 1990 as to the looming danger of greenhouse gases.

New passenger vehicles by type, United Kingdom. Taken from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/new-vehicles-type-share?country=~GBR

Other alternatives

Hydrogen passenger vehicles have also been in development since the late 1990s. However, there is a lack of infrastructure to make refuelling practical. Extracting hydrogen is energy-intensive and generally not carbon neutral. There is currently no cost-effective low-carbon fuel source to replace even a small proportion of the fossil fuel market.

Electrification is not the only solution. Reaching net-zero by 2050 will require fuel cells, biofuels and other yet-to-be-discovered enhancements. The consensus from organizations like the International Energy Agency, Hot or Cool Institute and Breakthrough Energy is that the electrification of light-duty road vehicles represents the best chance of significantly reducing CO₂ emissions by 2030.

Upstream emissions

Part of the climate math here is avoiding upstream carbon emissions. If we are plugging in instead of fueling up, those kilowatts need to be coming from green energy, or we are just swapping the emission source. Stephen Ferguson’s blog Keeping the lights on in a Climate Emergency explores this issue.

Making electric vehicles vastly superior

Drawbacks identified over a century ago are still not fully resolved. The same engineering ingenuity that addressed flaws and reduced the cost of early ICE vehicles is what EVs require now. The rise of SUVs complicates efforts to rein in auto emissions. Electrifying SUVs is much more complex than smaller vehicles. The additional battery capacity required further increases their weight (which reduces range), drives up their cost over conventional SUVs and prolongs the recharge time.

Batteries are at the crux of these limitations. The challenge is lowering their costs while also improving capacity and recharge times. Improperly shortening charge times can have deleterious effects, as the article “Improving battery fast charging experience while limiting battery ageing” explores.

Reducing the weight of electric vehicles is another way to extend their range. New composite materials that are light and less costly to mass-produce are needed. Simcenter offers multi-attribute solutions for composite materials, including multiscale simulation, allowing for predicting performance for lightweighting. Read more in “Composite Materials Performance Evaluation – using a fast, virtual testing tool“.

Charging infrastructure is also critical. It must become as ubiquitous and convenient as gas stations. There are calls for a greater degree of interchangeability between EVs.

At the heart of electrification are the electric motors and inverters. Simcenter solutions can help develop novel traction motors.

“We need to be adopting electric vehicles as fast as we bought clothes dryers and color TVs when those became available.”

Bill Gates, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster

Long-haul freight, aviation & shipping

There are limited solutions to decarbonize road freight, aviation, and shipping. At least those that would be practical and scalable. That is why companies such as Airbus explore a wide variety of options.

The weight of heavy-duty freight trucks makes electrification problematic. Gasoline has an energy density of about 46 M.J./kg. The densest battery (just cracking 1 MJ/kg) is still 30-40 times less than gasoline. The weight and space taken by the batteries to allow such trucks to be driven a reasonable time before requiring a recharge would reduce their cargo capacity up to 75%. Further refining current battery technology, such as lithium ions, is unlikely to yield the density required for freight. As a result, significant breakthroughs in battery technology would be needed to make electrification viable.

Electrification would be an option for smaller crafts that fly shorter distances. Cranfield University and Siemens Industry Software have partnered for aircraft propulsion electrification. However, marine, long-haul flights and larger aircraft electrification suffer from the same impracticalities as freight trucks.

Getting back on course

Set an ambitious target. Miss target. Set a new target.

To sum up, there isn’t much time left to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the worse impacts of climate change. A drastic acceleration in deploying carbon-zero technologies available is a must. It will take more engineering innovation to decarbonize all the different transportation subsectors and reach net-zero by 2050.

But, the question remains – can we hit the 20% reduction needed by 2030? If we lean heavily on passenger road vehicle electrification, the answer is yes, according to projections from the IEA.

There are significant barriers to EV adoption; however, it is within grasp with further innovations driven by Simcenter solutions.

And there are encouraging signs — the city Shenzhen, China, which has electrified its entire fleet of more than 16,000 buses and nearly 22,000 taxis.

Set an ambitious target. Reduce transport emissions by 20% by 2030. Make target. Set a more ambitious target for 2040 and beyond. Stay on course for net-zero emissions by 2050.

Global CO₂ emissions from transport by subsector, 2000-2030

Taken from – IEA, Global CO₂ emissions from transport by subsector, 2000-2030, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-co2-emissions-from-transport-by-subsector-2000-2030

Bringing the cost down through better engineering

Countries with higher EV adoption offer a tax credit or similar incentive to artificially bring cost parity to conventional vehicles. Without bringing the cost down through better design and engineering, further adoption will slow down if these incentives disappear. Our integrated and precise digital twin for electric vehicles addresses challenges for all vehicle domains.

You might also be interested in:

Engineers caused the Climate Emergency. Only engineering simulation can save us from it.

[1] Based on a daily average of 29.2 miles per day – https://newsroom.aaa.com/2015/04/new-study-reveals-much-motorists-drive/ [2] https://www.icao.int/annual-report-2019/Pages/the-world-of-air-transport-in-2019.aspx [3] Using the low-end long-haul flight rate of 150 g of CO₂ released per passenger-kilometre